Finance & Business

Author: anonymDate: 2024-11-21 10:58:35

The disparity in compensation between genders signifies that women, on average, provide unpaid labor from today until year's end.

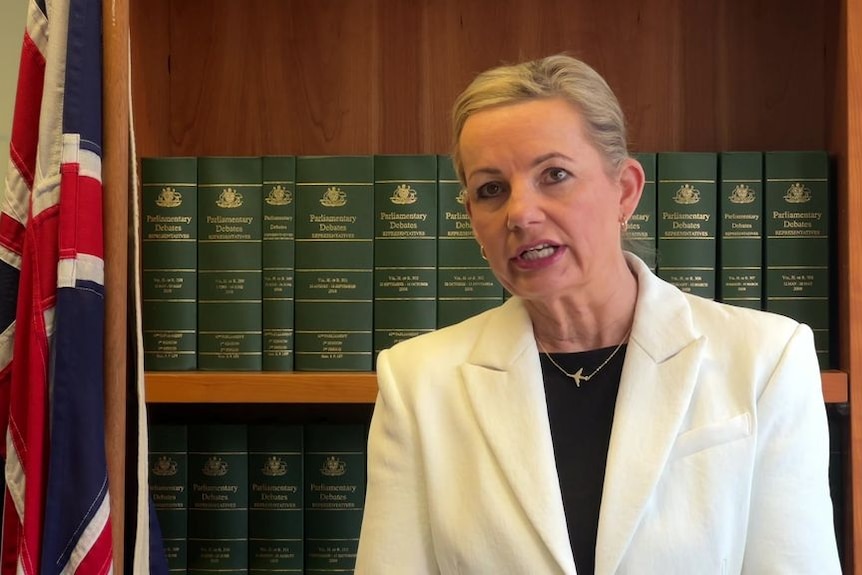

Cassandra Barratt says the gender pay gap has always been obvious in the early childhood sector but things are changing

Imagine toiling without compensation from now until December 31st. For the typical Australian woman, this is their current reality, reflecting Australia's gender wage differential. In certain industries, this impacts the majority of the workforce. Cassandra Barratt, administrator of an early childhood education center, plays a pivotal role in nurturing young lives. "I witness children's growth from infancy to school readiness, embarking on life's next chapter," she remarked. "It's incredibly rewarding." However, her nearly two decades in this field have starkly revealed the gender pay gap's harsh truth. "Professionals with similar qualifications in other sectors earn significantly more than those in early childhood education, primarily due to the female-dominated workforce," she explained.

“I've seen educators unable to meet housing costs or remain in the profession due to financial constraints,” she added. “They can't afford to continue. A truly exceptional educator I knew transitioned to driving a bus because it provided better financial stability for her and her family. Another became employed at a home improvement store.” Recent findings suggest that while the gap persists, it's closing considerably faster than before. Legislation enhancing worker rights—including flexible work arrangements, abolishment of pay secrecy, expansion of collective bargaining, and public disclosure of gender pay gaps—contributes to this improvement.

Working for 'nothing' from today

For half the population, today isn't just another day, according to Michele O'Neil, president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU). "Today marks the day women effectively begin working for free in Australia."

The peak body representing Australian unions attributes this to the gender pay gap—the average earnings difference between Australian men and women—standing at 11.5 percent.

“The disparity is substantial, equating to approximately 42 days of unpaid work annually for women compared to men,” Ms. O'Neil stated. The 11.5 percent figure originates from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, based on average weekly earnings for full-time adult employees. Part-time workers and overtime are excluded, making the actual gap significantly larger for most. The Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) also gathers data and calculates its own gender pay gap. They consider 'total' compensation, including bonuses and penalties, resulting in a 21.7 percent gap. Their conclusion is straightforward: "Women earn 78 cents for every dollar earned by men, resulting in an annual difference of $26,393."

But aren't we paid the same?

The gender pay gap quantifies the earnings discrepancy between genders within a business, industry, or nation. Many factors contribute to this ongoing disparity. Women have higher part-time employment rates, take more career breaks for caregiving, and disproportionately handle unpaid household chores. Historical discrimination, alongside lower wages in female-dominated sectors and jobs, play a role.

Aged care and early education pay rises help narrow gap

A new ACTU report reveals the gender pay gap is shrinking three times faster under the Albanese government than its predecessor, decreasing by 1.3 percent annually versus 0.4 percent previously. "For a nine-year-old girl, this translates to a nine-year wait for pay equity, rather than a 35-year wait under the prior administration's rate of progress,” Ms. O'Neil explained.

The ACTU, while independent of the government, isn't devoid of ideology—it generally aligns with and influences Labor Party policies. It actively campaigns for the Labor Party during elections. Business groups support narrowing the gender pay gap but oppose some industrial relations changes introduced by the government to achieve this goal. The ACTU report cites 20 factors contributing to this improvement, centered around: significant wage review outcomes benefiting female-dominated industries; strengthened rights to flexible work; increased pay transparency; and enhanced protection against discrimination and harassment. Among the most impactful changes were substantial wage increases in two female-dominated fields. Earlier this year, aged care workers received a pay raise of up to 28.5 percent. Early childhood educators, including Cassandra Barratt, received a phased 15 percent pay increase. The standard full-time weekly rate rises from $1,032 to $1,135 next month, increasing further to $1,187 by December 2025.

Multi-employer bargaining a win

These pay increases exemplify 'pattern bargaining,' where conditions are negotiated across an entire industry. Previously, industrial laws allowed only for individual enterprise bargaining between workers/unions and a single company. The federal government enacted these laws to empower small business workers, often lacking the bargaining leverage of larger unionized workforces. In their submissions, the Ai Group argued that multi-employer or 'pattern' bargaining was 'unnecessary and unwarranted'. They stated, “This expansion would diminish productivity, investment, and employment.” The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), while committed to closing the gender pay gap, opposed changes preventing salary discussions. The ACCI submission stated: “The legislation should clearly state that employers aren't obligated to disclose their pay or contractual details to those who request them. A ban on pay secrecy shouldn't mandate pay transparency.”

Many dimensions to the problem

Addressing the gender pay gap, like intricate challenges like the housing crisis or inflation, isn't a simple solution. “It’s difficult to quantify the impact of industrial relations reforms on the decrease in the gender pay gap,” explains Silvia Salazar, senior research fellow at the BankWest Curtin Economics Centre. “However, the pace of change is clearly accelerating.” A more realistic perspective is that women's wages are influenced by several factors. “Women with children experience long-term earnings impacts, often working part-time instead of full-time. There’s also the issue of women concentrating in low-wage sectors,” Dr. Salazar notes.

Another factor, “a more cultural one,” is ingrained discrimination stemming from historical imbalances and occupational segregation. “A single solution won't suffice. Addressing all contributing factors is necessary.”

Stepping back

Data indicates faster progress under the current Labor government compared to the previous Coalition administration. “We all must strive harder to close the gender pay gap,” says Sussan Ley, deputy opposition leader and shadow minister for women, emphasizing the Coalition’s prior commitment. “However, we should avoid politicizing the numbers while actively working towards its closure.”

Ms. Ley advocates for supporting women's choices. “I'm concerned this data suggests more women are returning to work due to financial struggles,” she says. “They're working harder, but it's often because they're falling behind.” Regarding the Morrison Government's record, Ms. Ley points to increased funding for WGEA, two consecutive 'women's budgets,' and a minister dedicated to women's economic participation. “(People) can rest assured that, if in government again, we would dedicate the same level of effort and support to women’s economic choices and closing the gender pay gap.”

February will reveal if big employers have improved

The gender pay gap won't vanish overnight. In late February 2025, the government's Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) will again release gender pay gap data for private sector employers with 100 or more employees. This second report will reveal progress made by major institutions, well-known brands, and individuals' employers. For the first time, WGEA will publish an average gender pay gap and include CEO compensation. Nearly 80 percent of Australian CEOs are male, and these roles typically command the highest salaries. For Ms. Barratt and her colleagues, these changes are beneficial, with the pay increase doing more than simply reducing the gender pay gap. "It allows them to save and not live paycheck to paycheck. It means they might be able to take a vacation for the first time in their careers," she stated.

“It's improving things significantly. The entire nation is paying attention now, and I think that's incredibly impactful.”