Finance & Business

Author: anonymDate: 2024-11-21 11:41:33

Why Australia lags in interest rate reductions

Both Treasurer Jim Chalmers and RBA governor Michelle Bullock have been under pressure to slow inflation

Positive developments: Despite persistent core inflation exceeding targets, a likely official interest rate decrease is anticipated within weeks. However, this reduction will occur in the U.S., not Australia.

Recent U.S. inflation data mirrored Australian figures. Headline inflation significantly decreased to 2.6 percent, slightly lower than Australia's 2.8 percent. This suggests substantial inflation control. However, core inflation in the U.S. reached 3.3 percent, marginally below Australia's 3.5 percent.

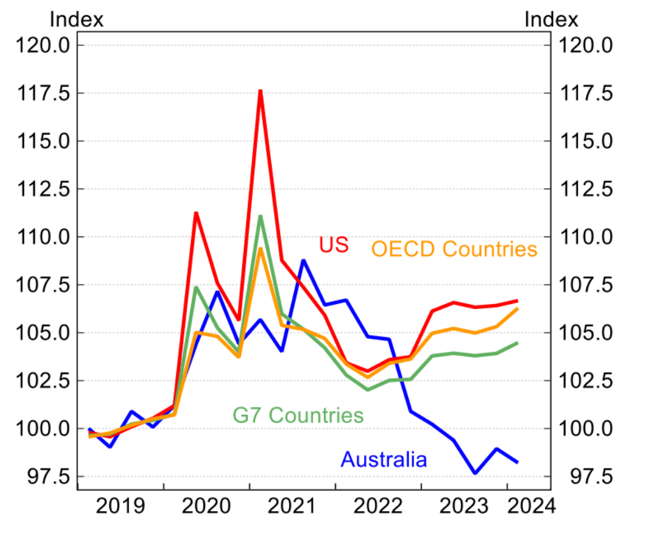

Share analysis Why Australia lags in interest rate reductions By chief business correspondent Ian Verrender Topic:Monetary Policy Sat 16 Nov Saturday 16 November A composite picture of a woman in black-and-white and a man in colour, both looking serious. Both Treasurer Jim Chalmers and RBA governor Michelle Bullock have been under pressure to curb inflation. (ABC News: David Sciasci) Link copied Share article Positive developments: Despite persistent core inflation exceeding targets, a likely official interest rate decrease is anticipated within weeks. However, this reduction will occur in the U.S., not Australia. Why Trump defeated the Democrats Photo shows Donald Trump smiles as he stands in front of an American flag.Donald Trump smiles as he stands in front of an American flag. Donald Trump's re-election was a revolt against economic policies that have left millions disenfranchised and uncertain about their place in the world. But Americans should be wary of his policies pushing inflation and debt even higher. Recent U.S. inflation data mirrored Australian figures. Headline inflation significantly decreased to 2.6 percent, slightly lower than Australia's 2.8 percent. This suggests substantial inflation control. However, core inflation in the U.S. reached 3.3 percent, marginally below Australia's 3.5 percent. The divergence lies in trends: U.S. inflation is rising again, while Australian inflation is steadily declining, as illustrated below. Following the U.S. data release, money markets projected an 80 percent probability of another rate cut at the next U.S. Federal Reserve meeting. These odds decreased on Friday due to reevaluation of a Trump presidency's inflation impact, yet a rate cut remains likely. In Australia, the situation differs. Market analysts and economists are delaying rate cut predictions as the RBA resists imminent reductions. A pre-Christmas cut seemed probable months ago, then February; now, May or later is possible after Governor Bullock's recent firm statement that further rate increases remain an option.

Why aren't we like everyone else?

Australian political dynamics often minimize subtleties. With an upcoming election, every advantage is sought. Both the Albanese government and the Reserve Bank faced pressure from economists and the opposition to control inflation. The RBA was previously criticized for insufficient interest rate increases, but is now condemned for its outlier status in maintaining rates amid global reductions.

The RBA had valid reasons for not mirroring U.S. rate increases. Australia is highly sensitive to interest rate changes because, unlike nations with fixed-rate loans, most Australian home loans are variable-rate. Thus, rate increases directly impact numerous households, forcing spending cuts.

The RBA also prioritized job preservation and resisted global trends. New Zealand implemented two rate cuts, but its economy is in recession, leading to emigration. Even post-cuts, its cash rate remains at 4.75 percent, exceeding Australia's. The U.S. also enacted cuts, yet its rate remains above Australia's (4.5-4.75 percent). The U.S. would need another cut to match Australia. However, concerns exist about potentially inflationary Trump administration policies impacting the U.S. ability to reduce rates, leaving Australia with comparatively lower interest rates.

Does lower inflation mean an end to the cost of living crisis?

No. While inflation is decreasing—the focus of politicians, economists, and the RBA—this doesn't mean lower prices. Price increases will merely slow down. Inflation measures the rate of price increase, not price levels. Therefore, even with normalizing inflation, costs will remain elevated; only the rate of increase will decrease. Wages may take years to recover lost household income. Australian households experienced significant disposable income loss, as illustrated by Commonwealth Bank data.

This results from Australia's variable home loan interest rate sensitivity. The Biden-Harris administration's election campaign made the fundamental error of conflating inflation and living expenses—an error the Albanese government seems to repeat, claiming the worst is over. Households are concerned about prices and affordability, not inflation. An interest rate cut—offering immediate relief—would be the most effective political message. However, governments lack direct control over central banks.

Why won't the Reserve Bank just cut?

Interest rate economic management is challenging. Proactive strategies are needed: raising rates preemptively and decreasing them as inflation subsides. While other central banks reacted to the inflation drop, the RBA's reluctance raises concerns about potentially excessively high rates as the economy slows.

The RBA cites low unemployment (4.1 percent) as evidence of economic strength, but wage growth has peaked and is declining (3.5 percent, down from 4.2 percent). Westpac chief economist Luci Ellis, a former RBA assistant governor, voiced concerns months ago, advocating for a November rate cut.

"It's not differing inflation views," she told SBS, "but the board's hesitation regarding proactive policy." Major banks predicted February rate cuts, but National Australia Bank retracted its forecast, delaying it to May. However, it reduced its variable rate due to increased home loan competition, potentially prompting other banks to act before the RBA.