Sports

Author: anonymDate: 2024-11-21 12:18:03

The extraordinary narrative surrounding Russia's unprecedented 110-4 defeat by Australia in the 2000 Rugby League World Cup.

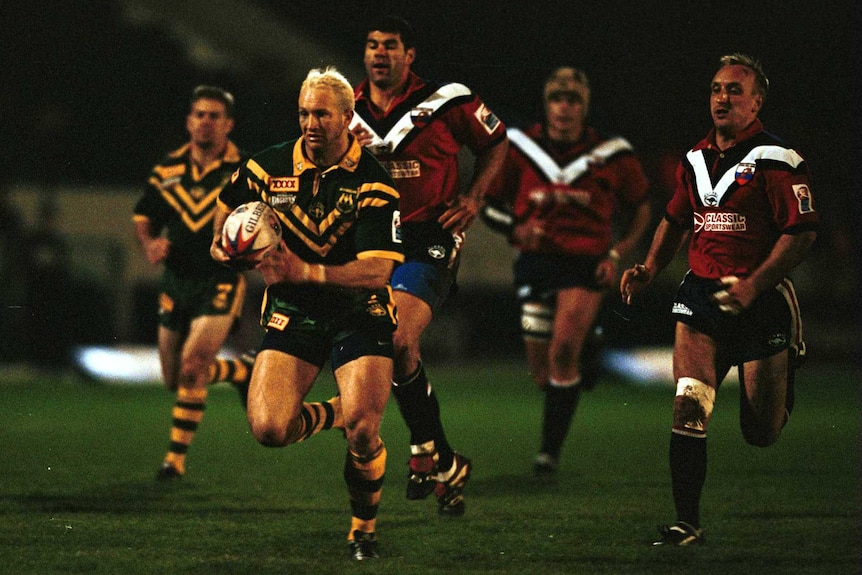

Shane Webcke is caught in the middle of a tackle as Australia took on Russia at the 2000 Rugby League World Cup.

Representing Russia in rugby league presents insurmountable challenges; however, Robert Campbell resolved to leverage this adversity. He doesn't precisely recall the score as Australia's triumph unfolded during the final group stage encounter of the 2000 Rugby League World Cup, but it was late in the contest, and this seasoned Gold Coast forward had a proposition for his distinguished adversaries. "Wagering on sporting events while participating is forbidden, but several acquaintances back home placed bets on Australia's victory by a margin exceeding 49 points—the highest odds offered by the TAB—and on Russia scoring precisely one, three, five, or seven points," Campbell explained. "During the rout, I decided to attempt a drop goal. "I was in a scrum, acquainted with some Australian players, and I requested proximity to the goalposts, explaining that friends back home relied on this. "They assented, but our players couldn't retain possession long enough! It would have been a significant gain."

Campbell occupied the front-row position for Russia that day at Hull's Boulevard and strived to remain unfazed by the Australians; however, his teammates faced considerable difficulty. For Kirill Kulemin, the youngest member of the squad at only 19 years old and a proud graduate of the Moscow Magicians, this was an exceptionally daunting Test debut. "Frankly, I shouldn't have been there due to my youth, but the coach advocated for me, and I was selected. What a horrific match for a young man!" Kulemin remarked. "Witnessing those renowned players opposing you is surreal—I had only seen them in videos provided by others. Satellite television access to NRL matches was unavailable."

“I donned a protective head covering before the game, a unique instance. I'm unsure why; I simply felt compelled to do something." By the final whistle, Australia had secured a 110-4 triumph over an assortment of amateur athletes from rugby league's wintry periphery. The match represents, and will likely remain, the most decisive victory in Test football history, concluding Russia's inaugural World Cup campaign. They might not participate again. In retrospect, their participation might seem illogical, but aspirations always maintain plausibility during their pursuit. The Russians suffered defeats in all three matches, accumulating a total score of 224-20, which was remarkable given the immense personal significance of the event for many participants.

Leather melon in the USSR

Rugby union boasts a more extensive history in Russia than many assume. Its introduction dates back to the 1880s, and by the 1930s, with the Soviet government's assistance, a national championship was established. Teams were managed through trade unions; while never a prominent sport, the game gained traction. By the 1960s, one hundred teams from thirty cities engaged in the activity, referring to the ball as the "leather melon." However, the Soviet Union's dissolution in the early 1990s and the resulting systemic dismantling hampered rugby's progress, leading rugby league to fill the void. "Numerous rugby players transitioned to the league format due to financial incentives offered by some teams, while rugby faced difficulties adapting to post-Soviet Russia," Kulemin stated. "The USSR's rugby championship was robust and featured talented players, but the sport struggled, creating an opportunity for rugby league."

“I didn't discover rugby; rugby discovered me. At a train station, a coach noticed a large individual and approached me about rugby—my knowledge extended only to the oval ball—but he insisted I possessed the necessary attributes," Kulemin recalled. "I was unaware of the two codes but started with rugby league. It evolved from a passion into my profession. In Russia, even at a young age, there exists a professional approach to sports—dedication is paramount. Daily training is the norm. "It's about community and distinctive experience. I developed a fondness for rugby: the camaraderie, the physicality, the team spirit." Kulemin began playing for the Moscow Magicians, a team within Russia's nascent competition, alongside others like Kazan Arrows and RC Lokomotiv Moscow. The league eventually grew to ten teams, ensuring automatic qualification for the 2000 World Cup, hosted in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and France. The Bears, as the national team was known, had competed since 1991, but required reinforcements; a search commenced for individuals with Russian ancestry and playing experience. This is where Campbell entered the scene. A resolute and skillful front-rower with experience at Wests, Illawarra, Gold Coast, and Widnes, he was playing for Redcliffe in the Queensland Cup when an opportunity arose.

“Tas Baitieri oversaw international programs, pioneering the involvement of emerging nations," Campbell stated. "Representatives of emerging nations visited Redcliffe, urging players to investigate their ancestry. A grandparent's identity or border shifts during World Wars I or II might suffice, and we discovered my eligibility. "Frankly, I believe they were seeking anyone with substantial playing experience at a high level.

“My grandfather was born in Poland, but following World War I, Russia annexed that region, establishing Belarus. "He hailed from Brest, located on the Mukhavets River near the border, and I maintained Polish heritage through my grandparents. "Mum, originally Maria Paulina Kaminski, immigrated here at age four, speaking no English; now Maree Campbell, she's utterly Australian. "Retirement was imminent. I was 29 and considered my career complete. My shoulders were severely injured; I played the last six weeks with injections, and we won the premiership. "Russia's offer arrived, and I anticipated three more matches." The towering Roosters prop Ian Rubin, born in Odesa, Ukraine, and an Australian teenager when he arrived, was the sole other player the Russians found with NRL experience; however, this was not due to lack of effort. Penrith fullback Peter Jorgensen declined due to a scheduling conflict with his wedding. Attempts to recruit Parramatta's Clinton Schifcofske failed as his Polish heritage stemmed from an ineligible region. The team included several Australians with Russian ancestry but no full-time professionals—Campbell was an apprentice plumber, and winger Matthew Donovan, inactive that year, worked at Hungry Jack's in Leumeah. The squad, assembled by coach Evgeny Kelbanov, faced 7500-1 odds of winning the tournament and traveled to the UK to compete.

'Not a single mass brawl took place without my participation'

Rubin and Campbell preceded the rest of the team, establishing an immediate presence. "We arrived a week earlier than the others, enjoyed some beers en route, and participated in a press conference with other captains. Everyone criticized us," Campbell recalled. "We were slightly intoxicated after consuming numerous beers on the flight, and the English press questioned whether we would be an embarrassment. "I responded, 'Listen, you'll be trounced by Australia, so refrain from criticism. You invented the game and are subpar, so leave us alone.' "Everyone began packing up, but my remark re-engaged media attention."

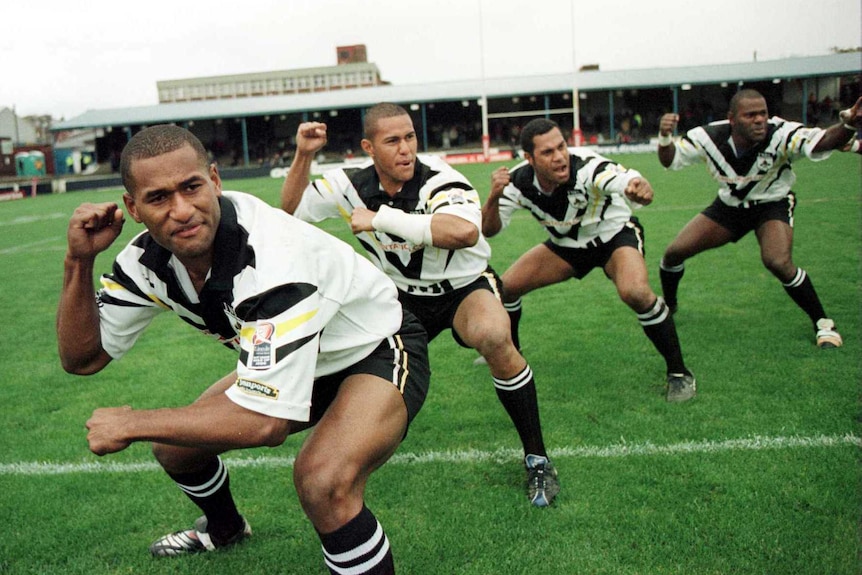

Subsequently, the Australians became acquainted with their counterparts from the rugby league's margins, gaining insight into their lives. In his 2017 book, Stuff You May Have Missed, commentator Andrew Voss dedicates a chapter to the Russians, with Campbell detailing the local players' employment as "police officers, military personnel, or mafia members," a reality that struck him forcefully. "We went to Sydney for a training session, instructed to retain receipts for reimbursement upon reaching England," Campbell explained. "Payment was received in pristine US dollars, and the daily allowance was consistent. "A bag was opened, revealing what seemed like Monopoly money, fresh and crisp, with tags attached. "The individual behind the financing held a poker machine license in Russia, suggesting considerable wealth. I suspect one wouldn't obtain such funding with a spotless record." Rubin was appointed captain and, speaking Russian, served as a bridge between the team's factions. With their tournament opener against Fiji approaching rapidly, the less-experienced players looked to their more seasoned teammates for guidance. "Rubes did his utmost for Russia. He shouldn't have played full matches because his usual approach was 20 minutes on, 20 minutes off, but he committed to playing as much as possible," Kulemin commented. "It was fascinating observing their playing style and teamwork. We didn't communicate extensively. However, they demonstrated proper gameplay."

Besides the Australian contingent and five-eighth Andrei Olari, a former Toulouse player, the entire squad hailed from Russia's domestic competition. They were raw but robust—tough utility forward Aleksandr Lysenkov was a soccer convert, and such stories were commonplace. "I could have followed a criminal path. During my youth, I was a notorious street thug, a menace in the Timiryazevsky district," he told Vladimir Suetin of the Russian newspaper Gudok in 2009. "No major brawl was complete without my presence. My encounters with the police were frequent. "Evgeny Klebanov, who rescued me, prevented imprisonment. Without him, disaster would have ensued. "However, thanks to coach Klebanov, the Lokomotiv club, and rugby in general, I became a law-abiding citizen. "I made my senior team debut for Lokomotiv in 1988 at 15. I'll always recall my first match, against Kiev's Aviator. I played against grown men. "The Ukrainians inflicted several beatings. However, I didn't flinch and retaliated. Afterward, no Aviator player dared touch me again." The players' physical attributes and strength, if not technical skill, impressed Campbell. "The forwards were exceptionally straightforward; their rugby background was apparent, as they didn't utilize feints or other maneuvers," Campbell stated. "Their competition was probably inferior to BRL reserve grade. But if you wrestled them, they could potentially kill you; they were large and powerful. "They were also tenacious. One player suffered a training injury, and I doubted his ability to walk again. After receiving injections, he recovered, exhibiting extraordinary resilience, as he went from immobile to outpacing everyone in sprints the following day. "Rubes speaks Russian, but I don't. My communication consists mainly of whistling, which I used to request the ball. "They were regimented, occupying the same seats at every meal, and deviating from this routine caused distress. "They were pleasant individuals, but I attempted to encourage relaxation."

No beer, just vodka

Coach Klebanov led the national team since its inception in the early 1990s; this chain-smoking Master of Sports did his utmost to prepare his team for the opening clash against Fiji. "He coached Lokomotiv and was an adept manager, selecting players from strong clubs and securing sponsorships," Kulemin noted. "I'm uncertain whether he was a good or bad coach, but he fostered team spirit, the key element in uniting us and creating a positive atmosphere." The lead-up to the match presented challenges. During the final practice session, the stadium's floodlights failed, necessitating training under vehicle headlights. The game plan was to maintain simplicity—at least, that was Campbell's approach. "It was unique and a rewarding experience, but I couldn't understand the coach's instructions before matches," Campbell remarked. "He'd write plays on butcher paper, and Rubes and I thought, 'Let's complete a set of plays and kick to the corners.'"

This wasn't a poor strategy against Fiji, considering the strong winds in Barrow. However, the Russians were unfazed, having played in deep snow at home. Despite losing 38-12, the result wasn't shameful; they scored two tries and trailed by a narrow margin at halftime. However, it served as a significant learning experience. "The squad's most talented player was Robert Ilysaov of Kazan. He possessed exceptional speed and athleticism, excelling as a fullback," Kulemin mentioned. "During the Fiji match, he ran down the sideline, aiming to score, but Lote Tuqiri pursued him. "Tuqiri initiated the chase far back on the field, catching and tackling Ilysaov. Then I realized the difference between us and NRL players. "We didn't have someone like Tuqiri in Russia." This promising result preceded their subsequent match, a confrontation with England, scheduled for just three days later. Nevertheless, Campbell found time for a beverage with the dedicated and vocal group of traveling Russian fans. "A supporters group accompanied us, and I experienced Russian culture firsthand," Campbell explained. "They brought containers of ice and drinks, predominantly vodka. "They were the fans; I asked if they preferred beer, and they replied, 'No beer, just vodka.' They were outstanding."

England sought redemption after a 22-2 defeat by Australia in London's tournament opener; Russia was well-prepared for their encounter at St. Helens.

The wrong end of the record

“The match against England, the prior week, was more inspiring than the Australia match; playing in the 'backyard' evokes the dream of defeating England, an uplifting thought," Campbell stated. "However, we were aware of the likely outcome." England emerged victorious with a 76-4 win; Russia scored only through Mikhail Mitrofanov's penalty goals. There was minimal time to reflect or analyze the events; Australia awaited, again within three days. Russia's prospects were deemed slim.

A familiar adage suggests everyone has a plan until confronted with adversity. Russia devised a strategy for the Kangaroos, orchestrated by Klebanov. The plan involved three hit-ups, a deep kick, and aggressive defense. Given some players' physical strength, this was plausible on Klebanov's butcher paper. As a young debutant, Kulemin was prepared to give his all. However, with 24 years of added experience, his assessment is blunt. "What a foolish game plan! The 110-4 score reflects this; slightly improved gameplay might have altered the result," Kulemin said. "At halftime, the Australian players on our team advised, 'We won't do this—don't give them the ball.'"

The majority of the game was a procession. This was an exceptionally dominant team even by Australian standards—they defeated New Zealand by 40 points in the final weeks later, and were recognized as one of history's greatest touring teams. On this occasion, Darren Lockyer and Brad Fittler were rested, yet they still fielded the world's best team, with Andrew Johns, Shane Webcke, and captain Gorden Tallis leading the charge. Wendell Sailor scored four of the team's 19 tries, and Ryan Girdler added three, along with 17 goals, for a personal total of 46 points. Viewing the video later gives a surreal impression; at times, their movement appears faster than the Russians'.

A crowd of over 3000 braved the conditions at the Boulevard but wholeheartedly supported the underdogs; the Threepenny Stand's wood was rumored to originate from Russian pine. The score at halftime was 50-4, but Russia scored when Campbell performed a dummy and grubbered the ball to Donovan, and the former Hungry Jack's employee executed the try. "Rubes and I weren't intimidated, having played against many Kangaroos previously, but we understood the challenge. This was why I attempted the kick; I figured, 'Why not?' Campbell said. "I worked on radio later and interviewed Dell. "He conducted the interview from a golf course, boasting about his four tries against Russia. "I retorted, 'No one cares; no one remembers; Dell, all people recall is your shift from your wing allowing us to score!' "At the tournament's conclusion, I intended to inform that English journalist that England didn't score a try against Australia, while we did."

Australia scored two tries in the match's final two minutes, exceeding 100 points and securing its place in rugby league history. For the Kangaroos, it was a minor note; for Russia, participation itself was a triumph, and they celebrated accordingly. "I had immense fun, but the Russian players were prohibited from drinking until the final match. Witnessing the ensuing chaos was unbelievable," Campbell said. "They all indulged, and eventually, factions clashed—I believe it was mafia members versus police officers. Rubes and I watched from the hotel bar. "They moved to the car park, returned bloodied, and resumed drinking; they resolved their differences, and afterward, all was well. It was intense, but what could one do?" As promised, this was Campbell's final match. Some Widnes fans from his time with the club obtained his boots from that night, and they may still reside behind a bar somewhere in northern England. For Kulemin, the tournament was merely the commencement; rugby league's future in Russia seemed promising for a time. Over subsequent years, they entered teams in England's Challenge Cup and their international team performed well.

Kulemin participated in their following Test match against the USA in Moscow in 2002, attracting a remarkable crowd of almost 30,000, and visited Australia twice to participate in the World Sevens tournament. Progress wasn't always smooth—the team was once banned from training near Randwick Army Base due to 'security reasons'—but these were exceptional times for the Russians, who enjoyed significant neutral support. "Rugby league sevens rules were unconventional. Weighing 120 kilos, I played against league backs! Unlike rugby, where I could compete for the ball in rucks," Kulemin explained. "But it was incredible; Aussie Stadium was packed; everyone cheered for Russia due to our underdog status. "It felt like a World Cup due to the presence of various national teams alongside NRL teams, and Australian rugby league differs significantly from the English game. "I was deeply proud. This motivated me to pursue professional play because I always strive for complete dedication." Eventually, funding depleted, rugby union regained momentum, and thirteen-man rugby's appeal waned. In 2009, Kazan Arrows and Lokomotiv Moscow, the Russian competition's leading clubs, switched to union. Around the same time, a conflict among administrators resulted in a Super League-style split. The national team persisted but has been banned from all competitions since 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine. "Several amateur teams exist, but the sport is not large. Most teams play rugby league and union. Too many egos and insufficient pure passion hindered the sport's revival," Kulemin stated. "I dreamed of playing professional rugby league but transitioned to rugby union professionally."

Kulemin's career is a Russian success story. After switching to rugby union in 2004, he competed at the highest levels across Europe for Agen, Castres Olympique, London Welsh, Sale Sharks, and Perpignan.

He also earned 33 caps for the national rugby union team and would have played in the 2011 World Cup were it not for an injury. Following retirement in 2014, he engaged in coaching, including serving as Russia's high-performance manager for the 2019 World Cup, and now works as a player agent in France. "Initially, I aimed to assist Russian players in securing international opportunities," Kulemin said. "However, it's challenging—Russia has a robust championship, and players are well-compensated, making it a significant decision. Now I represent French, Italian, and English players, and I find it enjoyable and rewarding to remain in this field.