Opinion & Analysis

Author: anonymDate: 2024-11-21 14:27:52

Marie Kondo's tidying method jeopardizes the cultural legacy of individuals with backgrounds like mine.

The organizing guru recommends throwing out objects that don't "spark joy" in the present. But those items could be treasures for the next generation.

The organizational expert, Marie Kondo, has created a lucrative enterprise by encouraging people to evaluate their belongings based on whether they evoke happiness— discarding those that don't. However, this presents a challenge for someone with a multifaceted identity such as mine: refugee, first-generation Vietnamese American, daughter, mother, writer, and family historian. Rigorously adhering to Kondo's advice during spring cleaning risks decisions that diminish familial history and cultural memory. Kondo's focus is on present satisfaction with objects, neglecting past or future implications. Our current understanding of our connection to possessions is incomplete, possibly inaccurate, since this relationship evolves with time and our identities change. Precipitous decisions to discard items could lead to later regret, both for us and our descendants who might have found meaning in them.

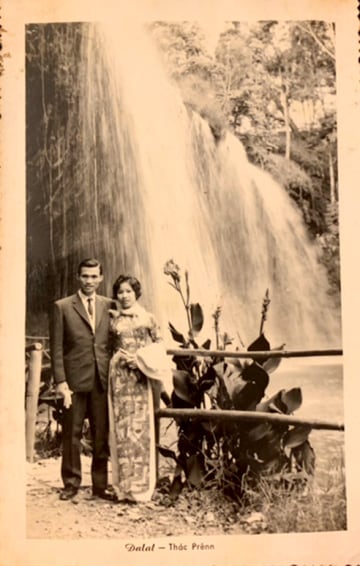

My family and I escaped Vietnam ten days prior to the fall of Saigon in April 1975, when I was thirteen. My grandfather served as an interpreter for the U.S. Army, and American officials facilitating our departure instructed us to bring only what fit in a small travel bag (6"x12"x14"). My mother chose family photographs, three of her beloved ao dai—traditional Vietnamese silk tunics—and love letters from my father. These possessions were lightweight, yet represented a world of prosperous, stable, and secure life to her.

Several years after settling in Virginia, she decided to donate her ao dai. She wasn't considering their historical weight, but how they painfully reminded her of a bygone era while she and my father, then legal immigrants, worked low-wage jobs to support our family of eight. Her once-bright vision of a perfect life likely caused her sadness and shame, resulting in the disposal of those lovely garments.

Naturally, "lovely" may reflect my sentimental view of the past. My mother simply stated the ao dai became incompatible with her American way of life. Her feelings towards her clothes changed with time, as she herself changed. Indeed, something once treasured may later become an unpleasant reminder of our unrealistic aims; conversely, objects evoking shame at one point may trigger insight later on. When deciding an item's fate, we choose between a burdensome past or losing potential future revelation. As displaced people, our relationship with material things is shaped by our new circumstances and historical forces, leaving us in constant change. Assimilation is a process of adjusting one's identity over time and space. Many immigrants view items acquired in their new home as superior to those from their former lives. A college roommate from India felt polyester was more sophisticated than her traditional Indian cotton dresses, discarding the latter soon after arriving in the U.S.

Even if we keep items for future generations, there's no guarantee they'll understand their value. They require historical background, particularly if the objects themselves are not inherently joyful or exciting. My mother keeps my brother David's Boy Scout uniform from around 1976. I never considered it significant until she explained my brother's happiness wearing it during our initial resettlement, enjoying the outdoors and adapting to elementary school. His successful integration into American society has been a source of pride for my mother. She keeps my brother's